The Past is Present

Left: The 38th parallel at the height of the Korean War. Right: Posing with my cousins after a cultural performance in Seoul.

The Side Project has one of the best intimate spaces in town. Its small size thankfully precludes large intimidating crowds, and though you end up practically face-to-face with the audience, the atmosphere had a nice, cozy salon feel, amply backed by Matt Wills' live music that night.

Given that

fatherhood has certainly altered (if not altogether restricted) my time pursuing performance, I've decided to share my piece in its entirety here on my blog. I wouldn't mind getting another crack at presenting it live sometime, but for now, here it is . . .

Yes/No

A language lesson. Yes, let’s start with a language lesson. Courtesy

of my father’s side. My Japanese side. The Japanese word for home is ie. Like saying the letters E and A. Ie. It shouldn’t be confused with the

word iie, which sounds very similar

but has an elongated vowel sound, the ii,

at the beginning. Listen very carefully: ie

and iie. Iie does not mean the same thing as ie. Iie is the Japanese

word for no. As in, “No, that is not correct,” “No, that can’t be done,”

and “No, you can’t come in here.”

A history lesson. No, iie,

an anecdote, courtesy of my mother’s side. My Korean side. In 2011, one of my

cousins on my mother’s side of the family was getting married. Yes, he had

gotten his fiancé to say yes, so he was going to be getting married in the city

of Seoul, in the Republic of Korea, the ROK, or as most Americans know it,

South Korea. A city that had been home to my mother and many of my uncles and

aunts for most of their childhoods through adolescence, until one by one they

made their way over to the United States for school and for work. Back then,

when they left, South Korea was under the authoritarian rule of Park Chung-hee,

a military strongman who had decided, yes, he’d be in charge, and seized

control through a coup d’etat following the deposition of Syngman Rhee, the

corrupt president installed by the U.S. after the Japanese were kicked out at

the end of World War II because the U.S. felt that, no, Koreans weren’t ready

to actually pick their own leaders and run the country by themselves. Post Rhee

and under Park, South Korea wasn’t exactly the land of opportunity, so despite

whatever love they had of family and country, my mother and her cousins decided

that, no, they couldn’t stay there, and departed those shores for elsewhere as

soon as it was possible. And away they went, finding homes in Hawaii, Ohio, New

York, Massachusetts and in the case of my mother, Illinois, yes, right here in

Chicago. Where she ended up saying, yes, and married of all things a Japanese

man. Well, no, not exactly. A Japanese man from Hawaii. My father. So, yes, here

I am.

Anyway, yes, there we were, my American-born cousins and I,

then, in 2011, 66 years after the end of Japanese occupation, 58 years after

the end of the Korean War, and 43 years after my mother said goodbye to my

grandmother, her brothers and her sister. My mother admitted to me that back

when she had left, the idea she would return to Korea would have been met with

a firm no. And who could have blamed her? Yes, she had plenty of fond memories

of growing up - of kind relatives and neighbors, of school outings and games,

but also plenty of sad ones. Of bombs dropping out of the sky during the war.

Of classmates lost or killed by stray ordinance. Of being sent home from school

one day in 1950, told by the teacher, no, do not return until the government

said, yes, it was safe, and it not being safe to return for three years. Of

losing her father, my grandfather, a communist, unfortunately, who when it came

time to choose sides, said no to the South, and yes to the other one, the one

now called the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or as most Americans know

it, North Korea.

But 2011 though was a different story. Korea, South Korea at

least, was booming. One of Asia’s “tiger economies”: fast, hip, stylish,

moddish, expensive and cooler than cool. The land of Samsung and LG, the

Hyundai and endless melodramatic soap operas exported throughout Asia and the

rest of the world. Only a year before Korean pop musician PSY would release his

“Gangnam Style” video online and become a bona fide cultural phenomenon. When

my cousin Hojung sent out his wedding invitations to all of us, I think it was

largely as a courtesy, the pro forma of an observant Korean relative, assuming

that maybe one or two of us might make the long flight overseas. Much to

everyone’s surprise, some eleven of us, including some spouses, ended up

RSVPing yes, and on top of us many of our parents ended up saying yes as well.

It would be an unprecedented family reunion back in the old

country. First one I could ever recall having in my entire life. And so, once

the RSVPs were in and everyone’s travelling dates set, my relatives spared no

effort in putting together a packed plan of action and activities, of tours and

trips about this glittery modern Asian metropolis of bustling streets and shiny

new buildings shooting up into the sky, glowing all colors at night like a

Blade Runner-ish fever dream.

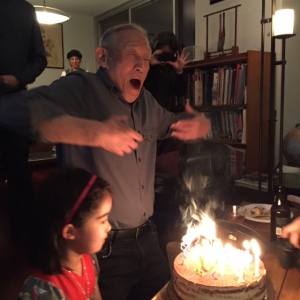

One of many family dinners.

We viewed the exhibits of the National Folk

Museum of Korea with its relics of the past, walked the grand grounds of

Gyeongbokgung palace, window shopped in Namdaemun market and even went to the,

don’t laugh, Kimchee Field Museum, where you could learn all there was to know

of Korea’s national dish. There was Sunday church with my grandmother, still

active in her 90s, at the very Methodist church founded by her father, my

great-grandfather. A trip to a cat cafe, a dinner where we literally ate like

kings at a restaurant that prepared dishes originally served only to Korean

royalty, and, of course, evenings full of Korean barbeque and the sounds of norebang, or as most Americans know it, karaoke. Yes, it was great.

On one of these days before the wedding, ten we spent in

total, a trip was organized to visit the Korean Demilitarized Zone, the DMZ.

The 38th parallel, which cuts the Korean Peninsula almost exactly in half into

North and South. The last true Cold War outpost, still very dangerous, just as

potent as ever, but like almost everything else in today’s Korea, a site for

tourists. Asked if we’d like to go, we all said yes. Why not, it’d be

interesting.

My cousins and I gathered early in the morning and boarded a

tour bus that would drive the 35 miles from South Korea’s capital to the

heavily fortified border. As the road wore on, the buildings became fewer and

fewer, the hills more and more numerous, and the road itself narrowing to the

single highway running between north and south. Those hills looked bleak and

bare, a reminder of the heavy deforestation wrought by the Japanese during

their occupation, the heavy toll of bombing and battle as Seoul was repeatedly

taken and retaken during the course of the Korean War by either side. The

landscape continued to transform. Barbed wire fences began to appear as part of

the scenery, as well as concrete structures straddling high over the road like

bridges, but weren’t bridges. Anti-tank defenses our tour guide explained. If

the north were to attempt to use the road to transport armor, these were rigged

to explode and come down.

There were several stops on the tour. Including the Joint

Security Area the JSA, the only place on the line where yes, North and South

could see each other face-to-face and talk to person, but also where, no, you

could not cross unless allowed. There were warnings given to our group. No, you

could not take photos of the North Koreans on the other side, especially the

soldiers. And no, do not point to them. We were even inspected for our

clothing, because if we were dressed inappropriately, no we would not be

allowed to approach the border. Apparently something to do with the North

taking our photos and using us for propaganda if we appeared too poor or sloppy

(No, don’t ask me, I can’t explain how that works).

Guards in the Joint Security Area (JSA)

There was something very strange about standing on that line

crafted by generals and politicians decades before I was born, deciding that,

yes, this was the best way to end the fighting, but, no, no one would ever

cross this way again. The people on the other side were not me or my cousins,

but they looked like me and my cousins. In fact they might have been other

cousins, albeit distant. At some time, long ago, my grandfather crossed over

that line, and no, never crossed back again.

At another stop there was a lookout, and using one of those tourist

coin-op binoculars you could see across the border towards the city of Kaesong.

Right now there’s an industrial park there, jointly run by north and south. A

positive step towards goodwill between the two governments. But Kaesong was

also home for several of my uncles and aunts in the Kim family before the war.

Somewhere over there was the land where their old family home once stood, a

traditional Korean home not unlike the replicas I had recently seen at the

museums in Seoul. Somewhere over there was a place members of my family use to

live and visit, but today, no, not any longer. Perhaps never.

At yet another stop we found ourselves at a train station.

Nothing historical, a big modern facility as gleaming and high-tech as the one

in Seoul. But quiet. Still. It was a remnant of a plan to eventually connect

the train system of the South with that of the North, during a time when

diplomatic relations were riding an all-time high. But then there were changes

in leadership, and the new leaders disagreed and said no, and the project

stalled. Looking at the station, my wife said it made her think of stories, the

old kind of stories you read about. Like a story about a family leaving a place

setting at the dinner table every night for a long lost relative, waiting, but

that long lost relative never coming.

On the ride back to Seoul, it only then occurred to me that

none of our older relatives had come along with us on the tour. I asked one of

my cousins why. “No,” he told me, “They don’t really want to be reminded of

this.”

It’s 2015 now. Four years since that trip. About half a year

since my son, my first child was born. Yes, I love him. And I love the fact

that, yes, all things being equal, he will be able to go about and move about

and see his family and the places he grew up unfettered and unfenced. That yes,

if we hop on a train, say the CTA Blue Line, and I take that trip out West,

waiting at the end will be my parents and the home where I grew up. That yes, I

can walk with him on the streets of my youth. And yes, I can hop in the car and

do the same on the streets of his mother’s youth. That yes, all the right faces

are open and places are open, and yes, that is one of the happiest thoughts I

can possibly have.

To which I say ne,

which sounds like the English word “nay,” as in “no,” but in Korean ne means “yes.”

So, ne.

Yes.

Yes.

Yes.

Dwight Sora, January 18, 2015