Cold Walk to the Dojo

Monday, February 2, 2018. A not-unfamiliar scenario for me. Trudging through snow and temps in the teens on a Chicago winter night to teach aikido. Making my way to the well-worn green and red mats of Tohkon Judo Academy, based within the Japanese American Service Committee building, where my dojo (Chicago Aikido Club) has made its home for the past five years or so.

Will there be anyone there? I wonder. Does anyone ever come on nights like this, other than the poor soul designated to try impart a little knowledge (or at least provide a workout) on that given night?

Why do I do this?

It's crazy right?

At this point in my life - mid-forties, married, one kid - devoting any time to an interest as fringey as "the Art of Peace" (as aikido is sometimes popularly called by its followers) does sometimes seem a bit futile; maybe even irresponsible. After all - and with the deepest apologies to my teachers, seniors, fellow students, and the wider world of Japanese culture for what I am about to say - in one sense it is an act of dress-up: Grown men and women (and occasionally children) wearing faux samurai outfits practicing esoteric exercises that may or may not deserve the label of being a "martial art"; married to gestures, rituals and etiquette mimicking supposedly traditional rules from a country half a continent and an ocean away (And probably not that well, if I think about it).

It's even less a practical pursuit than my other passion - acting. At least with acting I get paid, though not always terribly well, since I'm still largely confined to Chicago's (highly acclaimed but) not very lucrative storefront scene (I did have an agent WHO-SHALL-NOT-BE-NAMED who used to get me film and TV auditions before unceremoniously dumping me via e-mail two week's before my son's birth. Fatter opportunities have kind of dried up since then.).

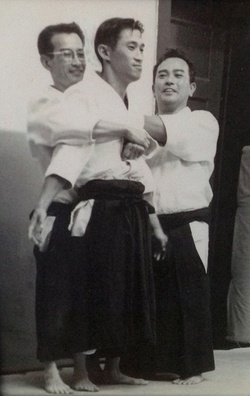

But here I am (or was, since now I am now comfortably sheltered from the cold within my north side apartment and a beer), prepared to do all the bowing, clapping, stretching, moving and calling-out-of-obscure-sounding-foreign-words that I have done since I (somewhat unwittingly) joined the Aikido club at Waseda University when I was an exchange student in the early 90s and found myself learning to toss people about or immobilize them against the ground.

Why do I do this?

A casual observer might think it's simply a matter of inertia. That strange force that sometimes keeps us in bad relationships and lousy jobs despite our better judgment. Like continuing to watch that long-running TV show you use to love despite the fact all the good actors have left and the storylines have become stale, repetitive and uninspired.

Insecurity? Ego? Certainly was true when I first started in Japan, where I discovered that my years of being an American couch potato reared on TV, snack foods and keeping my nose in books had ill-prepared me for the grueling physical regimen practiced by my Japanese college brethren. Not to mention the fact that despite looking the part, my Americanness (and perhaps I should add my half-Koreanness) were strikes against me. I was and am 99.99% sure they wanted me gone, and they worked me as hard as they could, but I absolutely, positively, assuredly refused to quit. First time in my life I had actually persevered in such a capacity, actually. And in the end, by the time I left to return to the states, I seemed to have gained a modicum of genuine respect (from myself as well as those around me).

Loyalty? A bit, I certainly don't like the idea of being a let-down to the senior instructors who've invested their teaching in me over the decades. Duty? I do feel some responsibility towards those junior to me that I give some of my time over to their learning and development (presuming they are maintaining their own interest and dedication).

But none of those really explain it all, or at least ring truest with how I feel, as opposed to how I think.

I continue to do aikido because it feels good. If I've had a long day working at my desk, chasing after my son, doing household chores, getting into uniform and stepping onto the mat never fails to make me feel better. Energized. Happier.

And it's not because I'm engaging in some cathartic act of sublimated violence. No, not that at all. Though, bodies hitting the floor is an unavoidable part of aikido practice. And I've been there - in the past, when I was younger, when I used the dojo as an outlet for daytime frustrations - at work, in relationships, unpleasant bozos on the street. No matter how much energy was expended, even if I got a bit of an adrenaline rush, whatever relief I felt was always a bit empty. Hollow.

Writing here, I find myself hesitating how to describe how aikido makes me feel good. Not because I'm afraid it will come across as hokey or unbelievable, or embarrassing for that matter. It's because it really does seem to defy easy description. I find myself thinking about Japanese writer Juichiro Tanizaki's seminal essay

In Praise of Shadows, where he summed up Japanese aesthetics as an appreciation of subtlety and shadow, as opposed to Western ideas of light and clarity.

On that note, I find my thoughts have run out of steam. Will ponder and perhaps return to this later.