Here's a little something I wrote up for Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month about Chicago Aikikai, the dojo where I practice the Japanese martial art of aikido. The original post may be found here.

“To practice Aikido fully, you must calm the spirit and go back to the origin.”

-Morihei Ueshiba, Founder of Aikido

Aikido, a martial way

May is Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, so it seems like a good time to turn back the clock and look at the Asian American origins of Chicago Aikikai and its place in bringing the Japanese martial art of aikido to the Windy City.

Martial arts are probably more ubiquitous than ever in U.S. pop culture, thanks to fighting-themed video games, superhero films and stunt heavy actioners like the John Wick series, and of course the multi-billion dollar industry that is Mixed Martial Arts (MMA). However, the success and widespread reach of these ventures has led most folks nowadays to associate the words “martial arts” solely with high-contact sports or violent maneuvers employed in imaginary street encounters.

Lost is the fact that, especially in the case of Japanese martial arts, there has long been a movement away from strictly studying practical fighting, and towards athletic and philosophical ends, not to mention spiritual and artistic (We’ll just skip their role in WWII militarism for now). Those whose only image of pre-industrial Japan is blood-soaked duels to the death informed by Rurouni Kenshin, the Zatoichi series and Akira Kurosawa period dramas might be surprised by the more than 200-year stretch of peace and stability known as the Edo period (1603-1868), during which most of the cultural touchstones considered characteristically “Japanese” in the West reached their pinnacle. Those would include flower arrangement, kabuki theater, ramen, sushi and budō (武道). Though usually translated as “martial arts”, budō is more appropriately read as “martial way”, the dō being the same Chinese character for Taoism, as opposed to bujutsu (武術): “martial techniques” used in actual combat.

In that sense, it would be appropriate to regard aikidō (合気道) and other budō as an expression of Japanese culture; the “art” part deserving as much emphasis as the “martial”. And I think that is important to note in light of who first brought it to places in the U.S. like Chicago and helped it to thrive. For those early days of aikido were still a time when many Japanese Americans were not always welcome to participate in mainstream sports and other activities; or to openly engage in practices that allowed them to be Japanese.

Connections, personal and not

2023 will mark my 30th year training in aikido, most of which has been at Chicago Aikikai. I am also fourth-generation Japanese American (or yonsei) on my father’s side and spent my entire life as a resident of the Chicago area (born in River Forest, attending University of Chicago, and now living on the north side). However, despite this, and the fact that Chicago Aikikai began as a Japanese American organization, I have no legacy ties. I joined in 1995, after graduating from University of Chicago, where the head of the on-campus aikido club, the late Professor Donald Levine, introduced me. Prior to that, I started aikido while attending Waseda University in Tokyo on the Great Lakes Colleges Association/Associate Colleges of the Midwest one-year Japan Study program.

I’m not even part of the same group of Japanese Americans who started the dojo (Yes, we have subdivisions), my father having arrived in 1959 from Kauai to attend Illinois Institute of Technology. Yet its history is a point of fascination for me and does elicit that strange sort of pride one gets from something you might share an ethnic kindship with, even if there is no direct connection.

Sadly, that history is gradually being lost day-by-day, year-by-year, person-by-person. Like most of the long-standing Japanese American organizations in town - from the Buddhist Temples to the churches to the social service organizations – it feels like those earlier generations were primarily concerned with working and surviving (as they should have been). So no real organized attempt was made to preserve and archive memories with the passing of time. Coupled with that was the gradual transition of the dojo from a rather informal community-centric club to an officially accredited entity [black belt ranks come from Aikido World Headquarters in Tokyo, via its national umbrella organization Aikido Schools of Ueshiba (ASU)], which went hand-in-hand with the joining of non-Japanese. Today, I’m really the only person of Japanese descent regularly training there.

When I was in my 20s, there were still a few holdouts from the old days. Joe Takehara, a now-retired dentist noted for his ability to make his body feel as solid as concrete while maintaining a state of relaxation, and Yuki Hara, a grandmotherly figure who inexplicably seemed to attend every camp and seminar across the country. However, they’re both retired now, taking their stories with them.

I sometimes feel like Chicago Aikikai is akin to the Nisei Lounge, “Chicago’s finest dive bar”, located in Wrigleyville. Nisei Lounge (taking its name from the term for second-generation Japanese Americans) was founded in 1951 back when Clark Street was part of Chicago’s Unofficial Japan Town. The nisei aren’t around anymore, but the current owners have kept the name and mementos of the bar’s past. The bar is also occasionally a venue for Japanese American community events.

In any case, here is a very incomplete history of the early days of the Chicago Aikikai and its Japanese American roots cobbled together from anecdotes, late-night talks over drinks and a handful of interviews. Special shout-outs to Joe Takehara and Erik Matsunaga.

Dwight Sora

Chicago, 2023

NOTE 1: I have chosen to begin my timeline with key events in the development of aikido in Japan and Hawaii to provide historical context.

NOTE 2: Given the fragmentary nature of my sources, I welcome anyone with first-hand knowledge who reads this, spots inaccuracies and can offer corrections. If you have anything, please e-mail chiaikikai@gmail.com.

Early history of Chicago Aikikai (originally Illinois Aikido Club)

1920s - Morihei Ueshiba creates aikido based on traditional Japanese martial arts.

1940 - Aikido is officially recognized by the Japanese government.

1948 - Aikikai Foundation and Aikido World Headquarters (Hombu Dojo) based in Tokyo, Japan is established.

1952 - Hombu Dojo begins dispatching instructors overseas to spread aikido.

1953 - At the invitation of the Nishikai Health Organization in Honolulu, Hawaii, Hombu Dojo sends instructor Koichi Tohei (1920-2011) to participate in a demonstration of Japanese martial arts. Impressed, many spectators take up training in aikido, first held on the grounds of the Nishikai. Tohei stays for one year, establishing many dojo in the islands, and making it a center for the art’s spread within the country. Tohei’s Hawaii students include instructors Isao Takahashi and his son Francis Takahashi. Tohei returns to Hawaii in 1955 and 1959 to further strengthen the aikido base he created.

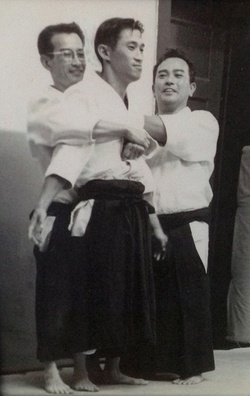

1961 - Norman Miyagi, a nisei (second generation Japanese American), becomes interested in aikido after reading a book by Koichi Tohei (most likely Aikido: The Arts of Self-Defense, 1957). Together with John Omori, they recruit other nisei by word-of-mouth and begin meeting privately to teach themselves aikido as a cultural pastime and for its mental and physical benefits. Rather than youthful dabblers, they are all established professionals in their 30s and older. In addition to Miyagi (an osteopathic physician) and Omori (an optometrist), the initial group includes Anthony Muranaka (a Chicago Police detective), Saburo Tanaka, Robert “Red” Sakamoto and Joe Takehara (a dentist).

- The group begins meeting in the storefront basement of Muranaka’s three-flat at 3324 N. Clark Street in the north side Lake View neighborhood. At the time the area is known as Chicago’s unofficial Japantown, a community of Japanese Americans that formed after WWII including transplants from Hawaii but mostly former wartime camp internees originally from the West Coast. The floor is made of marble and only 12' x 15', and the group trains without a mat. Lighting comes from a single ceiling light bulb; when it breaks, class is over for the evening.

- Through their Hawaiian Japanese connections, the group eventually makes contact with Chester Sasaki, a second degree black belt from Hawaii who is an undergrad at University of Illinois in Champaign. Under direction from Tohei and Hombu Dojo, Sasaki becomes their first official chief instructor. He makes regular weekend trips (3 hours each way) to lead all-day Saturday and Sunday classes.

- The group leases a street-level storefront on the next block at 3223 North Clark Street. They construct their first mat using purchased two-inch etherfoam. The resulting surface is much admired and used as a model for mats at several other Chicago dojo.

- There is no sign. The only advertising continues to be word-of-mouth, and entry to membership is limited. There is a board which interviews prospective students to evaluate their character. Most prospects are allowed in, but only after watching a few classes.

- In November, the group files with the state of Illinois to incorporate as a non-profit.

1963 - The group is officially incorporated as Illinois Aikido Club (IAC), thus establishing the Midwest’s first public aikido dojo. It adopts a circular logo symbolized by a circular mirror on a larger circular wood frame, forming part of the dojo’s shomen.

- Instructor Francis Takahashi (a childhood friend of Chester Sasaki from Hawaii) relocates to Chicago as a result of being inducted into the U.S. Army and is stationed here for two years. Sasaki is leaving the group due to graduating from University of Illinois and entering the Air Force, so Takahashi assumes the position of chief instructor.

1964 - Koichi Tohei teaches two seminars at IAC as part of a one-year tour of U.S. dojo.

1965 - Yoshihiko Hirata, a young sandan sent from Hombu Dojo, becomes the dojo’s third chief instructor and teaches until 1969, when he is inducted into the U.S. Army.

- Instructor Isao Takahashi, Francis Takahahi’s father, comes to Chicago from Los Angeles to serve as chief instructor of IAC. Takahashi alternates between the two cities, teaching aikido and iaido in Chicago for two months, and then returning to Los Angeles for a month. In his absence, Saburo Tanaka and Robert “Red” Sakamoto lead class in his place.

- Cheryl Kajita (later Matrasko), future founder of Aikido of Skokie, begins training at IAC.

Late 60s/Early 70s - Jon Eley (future instructor of Chicago Ki Aikido) and Frank Knapp are among the first non-Japanese to join the dojo, beginning a shift in membership demographics away from a majority Japanese American group.

1970 - IAC moves into a space in the Uptown neighborhood at 1103 W. Bryn Mawr. A former bowling alley that had been vacant for 20 years, it undergoes major renovation to create a dojo with a huge mat space - 45’ x 80’ feet.

1971 - Takahashi decides to retire to California. Hombu Dojo is contacted and instructor Akira Tohei is recommended to serve as new chief instructor and travels to Chicago from his then-current base in Hawaii to teach a summer seminar and meet with IAC’s Board of Directors.

1972 - Tohei relocates to Chicago to both serve as IAC chief instructor and establish the Midwest Aikido Federation (MAF). Isao Takahashi passes away on February 6 in Los Angeles at age 59 from stomach cancer.

- Charles Tseng (later founder of Lake County Aikikai) is invited to instruct at IAC by Akira Tohei.

1973 - Kisshomaru Ueshiba, son of Morihei Ueshiba and second Doshu, visits Chicago for the first time and teaches a seminar at IAC.

1975 - Tohei leaves IAC to form Midwest Aikido Center (MAC).

- Several guest instructors, including Terry Dobson and Robert Nadeau, teach at IAC on weekends.

- Mitsugi Saotome leaves his position as a senior instructor and Chief Weapons Instructor at Hombu Dojo and relocates to Sarasota, Florida in May at the invitation of local instructor Bill McIntyre. Saotome founds Sarasota Aikikai.

- That winter, Sarasota Aikikai hosts a 7-day camp starting on December 26 with instruction by Saotome and guest instructors Terry Dobson, Ed Baker and Frank Hreha. 85 aikidoka from around the country attend, 10 of which are members of IAC including Yuki Hara, Wendy Whited (later founder of Inaka Dojo) and Charles Tseng.

- Saotome establishes Aikido Schools of Ueshiba (ASU), an umbrella organization for dojo following his teachings.

1976 - IAC becomes a member of Mitsugi Saotome’s organization ASU and Saotome sends his student Shigeru Suzuki to serve as chief instructor.

1981 - Suzuki is forced to return to Japan due to health reasons. Kevin Choate is appointed the first non-Japanese chief instructor. He will hold this position until his death in 2012. He is succeeded by current chief instructor Marsha Turner.